Today’s post will be my first look into the life story of George Faulkner McMurry, one of the two brothers adopted by James Miller McMurry and his wife Grace Aitken. My cousin Crystal turned me on to this story, and if you haven’t read her post on George, you should go read it now!

Today’s post will be my first look into the life story of George Faulkner McMurry, one of the two brothers adopted by James Miller McMurry and his wife Grace Aitken. My cousin Crystal turned me on to this story, and if you haven’t read her post on George, you should go read it now!

Crystal learned that George and his brother Douglas survived a shipwreck that killed their parents. The brothers were then adopted by James and Grace McMurry in Port Townsend, Washington. She also learned that George was married briefly, and that he was murdered in San Francisco in June, 1945. All tantalizing stuff!

In addition to this story having a lot to recommend it on its own, I suspect that the story of George and his brother may shed light on Grace Aitken’s family in New York, and that it may help explain why widower James McMurry moved in his later years to Sutter County, California, where he apparently had no family.

This won’t be a full biography of George, but rather an exploration of a few documents I’ve recently found that advance our understanding of George a bit. The first document I’d like to present is George Faulker McMurry’s Petition for Naturalization and its accompanying documentation:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was interesting just discovering that this Petition for Naturalization exists, as George had previously stated that he was a U.S. citizen who had been born in New York City.

From his Petition for Naturalization, we finally learn the truth: George Faulkner McMurry was born on September 14, 1899, on the island of Curaçao in the Dutch West Indies. And he claimed that his full name at birth was George Talbot Faulkner (although as I’ll show below, this wasn’t completely accurate). He also stated that he was a British citizen by virtue of the nationality of his father’s mother.

George was 5 feet 10 inches tall, weighed 160 pounds, had blue eyes and brown hair, and had tattoos on both arms.

He also stated that he had gotten married to Fay O’Connor of Colorado on March 5, 1928, in San Francisco, California, but that they had since divorced.

According to the attached Form N-400, “Supplement Re Service On American Ships,” between May, 1918, and November 1943, George worked on at least 15 American ships that were over 20 tons, serving on at least 18 voyages on these ships, for a total of 7 years, 5 months, and 20 days at sea over that 25-year period. He may have been at sea even longer if he worked on any smaller ships or non-American ships.

George’s Petition for Naturalization was dated February 25, 1944. Why did he seek formal naturalization when he was nearly 45 years old, and not earlier? I suspect it had to do with World War II and an increased scrutiny being put on the citizenship of those serving on ocean-going vessels, but this is just a hunch.

According to the Petition for Naturalization, George emigrated to the United States in May, 1900, when he was only 8 months old. The ship he was on was the “G.B. Lockhart.” This is the ship that would later sink with George and his family aboard, taking the lives of his parents.

Now that we know that George was born in what was then called The Colony of Curaçao and Dependencies, a Dutch colony from 1845 to 1936, we can turn to the wonderfully organized, accessible, free, and mostly bilingual archives of the Netherlands, wiewaswie.nl. Sure enough, since George was born on Dutch soil, the Dutch have a record of his birth. And not just one record, but two records—one for when he was born with both of his parents’ names, and one registered 3½ months after his birth with just his father’s name and a statement that the father is aged over 50 years.

First birth record for George (click here for full record):

| Child’s name | De George Talbot Faulkner |

| Birth date | September 14, 1899 |

| Birth place | Willemstad |

| Father | Rupert de George Faulkner |

| Mother | Chrissie Harlan Jordan |

| Note | “Kind werd op 01-05-1900 (Stadsdistrict) erkend door zijn moeder en door Rupert De George Faulkner” (Child was recognized on 1 May 1900 (City District) by his mother and by Rupert De George Faulkner) |

Note that George’s full first name is De George, his father’s middle name.

Second birth record for George (click here for full record):

| Child’s name | De George Talbot Faulkner |

| Birth date | September 14, 1899 |

| Birth place | Willemstad |

| Father | Rupert de George Faulkner |

| Mother | NN (no name given ?) |

| Note | “Leeftijd vader is 50” (Aged father is 50) |

Willemstad is the capital of Curaçao, a charming Old-World-esque city that was founded in 1634.

The next document I found was George’s Application for Seaman’s Certificate of American Citizenship or Intention Papers, dated December 12, 1918, when George was 19 years old and just beginning his career as a mariner. The first thing you’ll notice about this application is that it contains two copies of a photo of a 19-year-old George:

|

|

|

|

On this application, George claims to have been born in New York City, and the Deputy Collector of Customs for Washington certifies that he has seen proof of George’s citizenship. While I have no evidence of this, I suspect that the Deputy saw a white, blue-eyed boy with an American accent and figured there was no cause to suspect that he was anything other than the U.S. citizen he claimed to be. It’s also possible that George didn’t know at this point that he was adopted, as he claimed his father’s birthplace was Illinois, which is actually the birthplace of his adopted father, James Miller McMurry. I don’t believe that was the case, however, as the 1910 census shows George and his brother Douglas living with James and Grace McMurry in Port Townsend, and has both George and his brother clearly marked as adopted sons (see detail image below). I find it hard to believe that they would freely disclose this to the census taker if they were trying to keep it secret from their sons.

Finally, from this application, we learn that one of George’s tattoos was an anchor on his right forearm.

I also found the 1930 census for George, which catches him living with his wife, Fay O’Connor McMurry, and her 15-year-old son John O’Connor (lines 33–35):

The G. B. Lockhart

I’d like to turn now to the ship that took the lives of George’s parents. According to page 188 of the Reports of the Harbour Commissioners for Montreal, Quebec, Three Rivers, Toronto, North Sydney, Pictou and Belleville: Report of pilotage authorities—Reports of port wardens, shipping-masters and of wrecks and casualties, the G.B. Lockhart was a 16-year-old wooden-rigged sailing ship registered in Windsor, Nova Scotia, Canada, when it was wrecked on May 31, 1906:

Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Volume 1, has additional information of the G.B. Lockhart (see line 4, below), including that the G.B. Lockhart was a 305-ton, 120 foot 8 inch vessel that was sailing under a British flag. And most importantly, the captain of the ship was listed as “R. de G. Faulkner.”

Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Volume 1, has additional information of the G.B. Lockhart (see line 4, below), including that the G.B. Lockhart was a 305-ton, 120 foot 8 inch vessel that was sailing under a British flag. And most importantly, the captain of the ship was listed as “R. de G. Faulkner.”

I haven’t been able to find any accounts of the wreck of the G. B. Lockhart so far, but I did find this one brief mention in the Report on the Trade and Commerce of Curaçoa for the Years 1905–06 by British Consul Jacob Jesurun (1907, pages 4–5):

Thanks to the Connecticut Digital Archive of the University of Connecticut, we have this gloriously large image of the G. B. Lockhart taken during a stop it made in New Haven, Connecticut:

The Connecticut Digital Archive’s caption for this print is: “Starboard view of the brigantine G. B. Lockhart at Canal Dock, New Haven, taken from Long Wharf. Buildings and smokestacks spewing smoke can be seen in the background.”

The shipwreck that killed George’s parents

The British Consulate in Curaçao recorded the deaths of George’s parents. George’s father Rupert is listed on line 5 of page 2:

George’s mother Chrissie is listed on line 1 of page 3:

A few interesting things to note:

- George’s parents, Rupert and Chrissie, are apparently the only deaths reported from in this document from the wreck of the G.B. Lockhart. As a wooden-masted sailing ship, Rupert would have needed a crew (other than his wife and two small children), so either there were crew members who survived the wreck, or they were not British subjects, so their deaths weren’t recorded on this British document.

- The wreck happened off the coast of Bonaire, an island just 40-50 miles east of Curaçao.

- The wreck and the deaths occurred on May 30, 1906, and the date given in the Lloyd’s register and in the Reports of the Harbour Commissioners is the following day, so these references were probably recording when they received notice of the wreck, not when the wreck actually occurred.

- Chrissie’s death certificate lists her name as “Chrissie Harlam Sears,” but George’s birth certificate lists her name as “Chrissie Harlan Jordan.”

I had seen that other researchers have looked for contemporary news accounts of the sinking of the G. B. Lockhart without success, but I thought I’d give it a shot anyhow, given the rapidly increasing number of digitized newspapers becoming available. And sure enough, after a short while I discovered the Caribbean Newspaper Digital Library site and saw that they had digitized issues of a historic newspaper from Curaçao for the years 1884 to 1986. What a glorious time to be alive!

Taking up nearly all of page three of the June 2, 1906, issue of Amigoe Di Curaçao was an account of the sinking of the G.B. Lockhart:

If you don’t read Dutch, what follows is the best translation I’ve so far been able to muster (if you do read Dutch, please let me know in the comments section below of any errors in my translation):

| „G.B Lockhart” [su_spacer size=”5″]Het treurig bericht van het vergaan van deze schoenerbrik zal onzen lezers reeds bereikt hebben. [su_spacer size=”5″]De volger.de bijzonderheden hebben wij van een der geredde matrozen vernomen. [su_spacer size=”5″]Het was een hooge zee, er liep een steike stroom, terwijl telkens valsche rukwinden de golven over het schip joegen. De brik was niet bijzonder zwaar geladen, zoodat het sturen bij zulk een weer zeer moeilijk viel. De nacht was buitengewoon donker; zware, zwarte wolken beletten ons de sterren te zien. Drie mannen werden uitgezet op het dek om te waken en goed toe te zien. De 7 overigen waren allen beneden. Opdat de brik níet al te snel zou varen, en men dus meer kans zou hebben ver van de kust verwijderd te blijven, reefde men alle groóte zeilen, en hield de fok met nog twee kleine zeiltjes op. [su_spacer size=”5″]Plotseling omstreeks vier uur in den morgen ziet een der matrozen, een Curagaonaar, Federico de Lannoy, heel dicht bij, iets zwarts vlak voor het schip. Voordat hij nog kon uitmaken of het land, of een hooge golf was, had de brik al op de rots gestooten. Op hetzelfde oogenblik vliegt de kapitein naar boven met zijn vierjarig kind in de armen en werpt het in zee, terwijl Federico reeds over boord was gesprongen, welk voorbeeld onmiddellijk door de andere matrozen was gevolgd. Federico moest op het geschreeuw van den kleine afgaan, daar hij geen hand voor oogen kon zien; hij was zoo gelukkig het kind te grijpen, sloot het in zijne armen en worstelde met mannenmoed tegen de golven, die hem het voortgaan over de scherpe, puntige rotsen bijna onmogelijk maakten. Zijn bloote voeten werden aan alle kanten opgereten. Ook de kleine schramde en sneed zijn voeten open aan die spitse, ijzerharde steenen. Goddank, kwam Federico behouden aan’t strand met zijn kostbare vracht. Hier ontdeed hij zich van zijn kleedereu, wierp die over het kind en sprong weer in het water, daar hij van alle kanten zijn naam hooide roepen om hulp en redding. De angst, waarmede hij zich opnieuw aan die woedende golven overgaf, is onbeschrijfelijk, want toen hij nauwelijks met het kind van boord was, hoorde hij een vreeselijk gekraak en biak de eene mast na den andere, stortte op het dek en plofte in het water. Het schip lag heelemaal over zij en al heel spoedig werd de achtersteven van het schip afgeslagen en de geheele brik aan splinters. [su_spacer size=”5″]Door schrik overmeesterd wisten sommige matrozen niet, wat zij doen moesten, terwijl de hooge golven rondom hen en de scherpe, ala bajonetten stekende rotsen onder hen, hun bijna iedere heweging onmogelijk maakten. Federico hield een der matrozen vast, die onmogelijk verder kon, en hem smeekte een oogenblik te rusten, daar hem het voortgaan onmogelijk was. Maar lang kon men niet stilstaan, op zulk een scherpe bodem, te midden van zulk een hevige branding. Eindelijk was de geheele bemanning gered en het schip verspaanderd uit elkander gedreven of gezonken. [su_spacer size=”5″]Toen het licht begon te worden en men in de verte een huisje zag, kwam men tot de ontdekking, dat men op Bonaire was gestrand. Al spoedig kwam Pater B. Krijgers, Pastoor van Rincón, ter plaatse om te zien, of zijn hulp ook noodig mocht wezen. Ook de districtmeester, de heer de Cadières, was reeds aangekomen, nam de namen op en zorgde voor schoeisel en kleederen. [su_spacer size=”5″]De geredde bemanning is vol lof voor alle hulp en medelijden op Bonaire ondervonden. De Bonairianen wisten niet, wat zij doen moesten om toch maar hun goed hart te toonen en de bemanning wat op te beuren. De matrozen rilden nog van angst en waren als half versuft door al de uitgestane ellende. De persoon, met wien wij spraken, kon zich nog niet volkomen alles herinneren, en had nog den schrik onder de leden. [su_spacer size=”5″]Woensdag tegen den middag tegen elf uur spoelde het lijk van de vrouw van den kapitein aan, met een groot gat in het achterhoofd, en’erg aan “de zijde gekneusd, waaruit men afleidt, dat zij met den kapitein door de vallende masten getroffen werd. Van den kapitein is nog geen spoor ontdekt, het lijk van zijn vrouw werd op Bonaire begraven, na het eerst van een ketting met medaillon ontdaan te hebben om ze naar New-York te sturen. [su_spacer size=”5”]Tegen drie uren ging de bemanning van Rincon naar de Oranjestad, waar zij vol medelijden ontvangen werden door den Gezaghebber H. Statius Muller, die voor plaatsen op de Christiansted, welke juist voor anker lag, had gezorgd. Zoo stoomden alle geredde matrozen Donderdag- morgen onze haven binnen, waar de Amerikanen een onderdak en liefderijke verpleging vonden op het politie-bureau. [su_spacer size=”5″]De andere Curagaonaar, welke gered is, heet Lucien Welhous en was reeds 10 jaar kok op de Lockhart. Federico de Lannoy is pas een paar jaar op dezebrik heet Lucien Welhous en was reeds 10 jaar kok op de Lockhart. Federico de Lannoy is pas een paar jaar op dezebrik. Het is voor de derde maal, dat hij een schipbreuk medemaakt. [su_spacer size=”5″]Wel toevallig, dat de Lockhart juist verging gedurende zijn negentigste reis, evenals de Curaçao, een brik van dezelfde maatschappij, nu tien jaar geleden. [su_spacer size=”5″]De lading, waaronder 3000 kilo dynamiet en carbiet, bestemd voor onze mijnen, was verzekerd, niet echter het lijfsgoed der bemanning, waar natuurlijk niets van gered is. [su_spacer size=”5″]Wij hopen, dat aan de bemanning een kleine vergoeding voor deze schade zal gegeven worden, terwijl aan Federico de Lannoy wel een bijzondere onderscheiding mag worden uitgereikt. [su_spacer size=”5″]De gevaarlijke lading, dynamiet en carbiet, ligt natuurlijk in de zee verspreid tusschen de overige lading van meel, gezouten vleesch, kerozine etc. Dat men nu toch niet de onvoorzichtigheid hebbe, naar de gestrande goederen te visschen, of te duiken en zooals de Procureur- Generaal waarschuwt, dat men voorzichtig zij, wanneer hier of daar kisten of blikken, mogelijk van de Lockhart afkomstig, aanspoelen. Men waarschuwe steeds de politie, om nog meerder onheil te voorkomen. [su_spacer size=”5″]Wanneer zal op dezen „doodenhoek” van Bonaire eindelijk eens een lichtbaken geplaatst worden? |

“G.B. Lockhart” [su_spacer size=”5″]The sad message of the perishing of this brigantine schooner will have reached our readers already. [su_spacer size=”5″]The following are the details we heard from one of the rescued sailors. [su_spacer size=”30″]It was a high sea, running a swift current, with strong gusts over the waves chasing the ship. The brig was not particularly heavily loaded, so that steering the ship became very difficult when such weather struck. The night was extraordinary dark; heavy, black clouds prevented us from seeing the stars. Three men were ordered onto the deck to watch and watch well. The seven others were all below deck. So that the brig would not sail too fast, and therefore be more likely to find itself far removed from the coast and stranded, the main sails were struck and only two small sails were kept up. [su_spacer size=”30″]Suddenly at about four o’clock in the morning, one of the sailors, a Curaçaoan, Federico de Lannoy, saw something black very close to the ship. Before he could decide whether it was land or a large wave, the brig had already hit the rock. At the same time, the captain flew upwards with his four- year-old child in his arms and threw him into the sea while Federico had already jumped overboard, an example which was immediately followed by the other sailors. Federico had to find the small one by listening for his screams, since he could not see the child’s hands; he was so happy to finally grab the child, and wrapped the child in his arms and struggled with a man’s courage against the waves that pushed over the sharp, pointed rocks—almost impossible. His bare feet were torn up on every side. All the little scratches from those pointed, hard-as-iron stones cut his feet open. Thank God, Federico reached the beach with his precious cargo. Here he took off his clothes, threw them over the child and jumped back into the water, where he heard his name called from all sides begging for help and rescue. The fear with which he rejoined those raging waves is indescribable, because when he was barely on deck with the child, he heard he a terrible cracking and one mast after another broke and collapsed on the deck and plopped into the water. The ship was completely turned over and soon the stern was broken away from the ship and the whole brig turned to splinters. [su_spacer size=”195″]Some of the sailors were not over- whelmed by fear, and did what they had to do, while the high waves around them and the sharp, stinging rocks like bay- onets among them, making almost every movement impossible. Federico found one of the sailors stuck so much that it was impossible to do anything further, and begged of him a moment’s rest, as it was impossible for him to continue as he had. But one could not stand still long on the sharp ground, in the midst of such a violent storm beating down. Finally the whole crew was rescued and the ship was broken apart or sunk. [su_spacer size=”80″]When morning light began to break and they saw a little house in the distance, they came to the realization that they had been stranded on Bonaire. Very soon Father B. Krijgers, pastor of the town of Rincón, came to the spot to see if his help might also be needed. The mayor, Mr. de Cadières, had also already arrived, and took the names of the survivors and provided them with footwear and clothing. [su_spacer size=”27″]The rescued crew is full of praise for all the help and compassion they encoun- tered on Bonaire. The Bonairians didn’t know what they could do, but they did what they could to show their good heart and brighten up the crew. The sailors still shivered from fear and were half-dazed by all the misery. The person with whom we spoke could still not completely remember everything, and was still frightened along with the other crewmembers. [su_spacer size=”7″]At eleven o’clock on Wednesday morning the body of the captain’s wife was found, with a big hole in the back of her head, and bruises on her side, from which one deduces that she and the captain were hit by the falling masts. While no trace of the captain has yet been discovered, the body of his wife was buried on Bonaire, after which a necklace and medallion were sent to New York. [su_spacer size=”80″]The crew went at three o’clock from Rincon to Oranjestad, where they were received full of pity by Lieutenant H. Statius Muller, who took care to find room for them on the Christiansted, which is anchored there. So all rescued sailors will steam Thursday—tomorrow—for our port, where the Americans will find shelter and a loving nursing staff at the police station. [su_spacer size=”55″]The other Curaçaoan who was saved is Lucien Welhous, who has been a cook on the Lockhart for 10 years. Federico de Lannoy had only been on the ship for a couple of years. This was the third time that he was involved in a shipwreck. [su_spacer size=”100″]It happens to be that the Lockhart, which was his ninetieth journey, had similarities with the Curaçao, a brig from the same company, that was lost ten years ago now. [su_spacer size=”2″]Its load, which included 3000 kilos (6,600 pounds) of dynamite and carbite for our mines, was insured; however, the life of the crew was not, and of course nothing was saved from that wreck. [su_spacer size=”2″]We hope that a small fee for this damage will be given to the crew while Federico de Lannoy deserves a special award of distinction. [su_spacer size=”53″]The dangerous cargo, dynamite and carbite, of course lies in the sea spread between the other cargo of flour, salted meat, kerosene, etc. That one is not care- less with the stranded goods found when fishing or diving, the Attorney General warns that one should be cautious when one finds crates or cans washed up that may be from the Lockhart. Always warn the police to prevent more misfortune. [su_spacer size=”105″]When will this “corner of death” of Bonaire finally have a light beacon placed upon it? |

George would have been 7 years old at the time of the wreck, but the story talks about his father Rupert throwing a 4-year-old child into the sea, so I’m guessing that at 7 years old, George was better able to fend for himself, and the 4-year-old thrown into the sea was George’s younger brother Douglas.

Let’s look a bit more at George’s biological parents.

George’s father Rupert

While in his late teens and early twenties, George’s father Rupert trained to become a ship’s captain. He was awarded his Certificate of Competency as a First Mate on July 9, 1870, in Liverpool, England, where he was living at the time:

A year later, Rupert was awarded his Certificate of Competancy as Master, issued on April 5, 1871, in Liverpool, England, where he was living at the time:

A deeper look into Rupert’s family and history will have to wait for a future post, given how much else I’m covering in this post.

George’s mother Chrissie

Christina (“Chrissie”) Harlan Sears was born in September 1867, in New York City, probably in Brooklyn) to Thomas A Sears and Freelove Ada (Douglas) Sears. While she would later contend that she was born a few years later (ca. 1870), the 1875 New York census clearly shows her as an 8-year-old girl with a 14-year-old sister, Kate D. Sears (page 64, lines 33–36):

Her father was a clothing merchant, and he owned land (presumably the brick house they lived in at 292 134th Street in Brooklyn).

By the time of the 1880 census, taken on June 5, 1880, Chrissie’s family was no longer living in their brick house, but were instead living in a boarding house at 55 Concord Street in Brooklyn. Chrissie’s father was still working as a clothing merchant, and a third daughter, Grace Sears, had now joined the family:

Chrissie married Francis “Frank” Emery Jordan on March 1, 1887, when she 19 years old. By the time of the 1900 census (shown below), enumerated on June 15th, Frank and Chrissie had been married 13 years and have two children—10-year-old daughter Ada S. Sears, and 7-year-old son Frank Atwood Sears. Frank’s occupation was recorded as “Sea Captain,” and Frank and Chrissie were now living in her parents’ house along with her unmarried 38-year-old sister Kate. Both Chrissie and Kate were now stating that they were born 3–4 years later than they actually were.

At some point between the June 15, 1900, and December 3, 1901, Chrissie and Frank got divorced. At this point, I don’t know what became of their two children—11-year-old Ada and 8-year-old Frank—immediately after the divorce of their parents. By 1910, however, a 20-year-old Ada had moved to Barnstable, Massachusetts, married a man named Eugene Adams, and had a daughter with him around 1910 that they named “Chrissie.” By 1910, a 17-year-old Frank was living with his maternal aunt, Kate Sears, and his grandfather, Thomas Sears.

According to their marriage record in the Netherlands Civil Marriage Index, a divorced Chrissie married a widowed Rupert on December 4, 1901, in Curaçao.

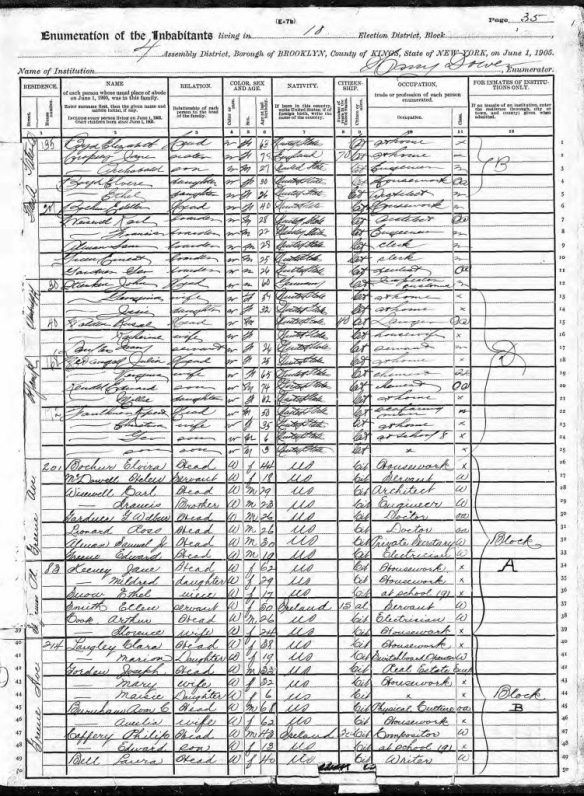

At the time of the 1905 New York State census, we find Rupert and Christina Faulkner married and living in Brooklyn at 172 St. James Place. They now have two sons—6-year-old George Faulkner and 3-year-old Daniel Douglas Faulkner (the latter just called “son” on this census):

Still left unresolved

-

The Relationship of George Talbot Faulkner to Grace Aitken

- I haven’t so far been able to find any relationship between the families of Grace Aitken and either Rupert Faulkner or Chrissie Sears, but it seems most likely that the it’s the Sears and Aitken families that will cross paths, as Rupert’s time was largely spent in England and Nova Scotia.

-

More details on the life and family of Rupert de George Faulkner

- I know from his marriage record to Chrissie that his parents were David Weir Faulkner and Hannah Beekwith. From Rupert’s time and training in Liverpool, and from George’s statement that he had British citizenship on account of his paternal grandmother being British, I believe that Hannah Beekwith was British, perhaps from Liverpool.

-

The murder of George Faulkner McMurry in 1945

- So far I haven’t found any evidence concerning his death or its cause, but I’ve had so many other topics to look into that I haven’t tried terribly hard, either.

Well, thank you for surviving another post. If you have anything to contribute about the story of George Faulkner McMurry, his background, his adoption, or the relationship between the Faulkners/Sears family and the Aitkens/McMurry family, please let me know in the comments section below.

Hopefully with two McMurry cousins on the case, we can get to the bottom of George’s fascinating story. Crystal—tag, you’re it!

The Hantsport & Area Historical Society just uncovered a newspaper clipping concerning the loss of the “G. B. Lockhart” and the drowning of Rupert de George Faulkner and his wife. It is dated May 1906 and attached to the link given below. He was first married in England in 1871 and had two daughters, one born in Brooklyn, New York and one died as an infant in Curaçao. His brother Delancey T. Faulkner was mayor of Hantsport at the time. I have just located Rupert in the 1871 census for Falmouth, and working on the family stumbled on this excellent article.

Thank you! Could you try posting that link again? It didn’t make it through in your comment. Am looking forward to reading it.

Hello Michael:

Here is the link to our recent article on the 1906 wreck of the “G. B. Lockhart”. Only the younger of the two brothers, 4 year old Douglas Faulkner was on board and rescued.

http://mcdadeheritagecentre.ca/2020/08/08/g-b-lockhart-wreck-1906/

Regards,

Leland Harvie for The Hantsport & Area Historical Society